- Home

- Georgie Newbery

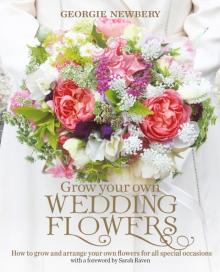

Grow your own Wedding Flowers Page 5

Grow your own Wedding Flowers Read online

Page 5

Thursday evening

Cut all flower stems.

Put to one side, clearly labelled, the flowers you’ll use for the bride, bridesmaids and buttonholes.

Leave all flowers and foliage to condition in tall, clean buckets of fresh water until you’re ready to arrange them on Friday.

Friday

Start arranging your flowers in the morning. Do the ceremony flowers first, then the reception flowers, then the buttonholes and the bride’s and bridesmaids’ bouquets. Make the bride’s bouquet last, because you’ll become very practised through the day. Try to get all the arrangements finished on Friday.

If you can install the flowers in the venue on Friday, do so, but only if the venue is cool. A hot tent overnight won’t do flowers any good. If your ceremony or reception will take place in a marquee, then I suggest you keep the flowers somewhere cool the night before and only install them on the Saturday morning.

Large arrangements can be spritzed with water to keep them looking fresh.

Saturday

If the weather’s hot, then the flowers might do well to have fresh water on the morning of the wedding: not only will this keep them fresher, but in hot weather flower water can go yellow, which isn’t as attractive in glass as perfectly clear, clean water.

Wednesday and Thursday

At Common Farm, we cut flowers all day long, all year round. It takes three of us about 2 hours to cut 1,000 stems. You will be nothing like so speedy with your scissors, so I suggest the following schedule.

Cut the foliage for your wedding flowers on Wednesday evening, and the flowers on Thursday. Two hundred stems of foliage cut on Wednesday can sit happily in buckets until Friday. Four hundred stems of flowers is a perfectly manageable number for you and perhaps two or three friends to cut together on Thursday evening. Give each of your helpers a list of what you need them to cut, and strict instructions as to how you want them to cut – stem length, how open your flowers should be, and so on – and you can all set off to cut the flowers, leaving somebody else to cook you supper and provide a cool glass of wine when you’ve finished.

Practice makes perfect. If you’ve practised cutting and tying and arranging some samples of your flowers (see ‘How to make a hand-tied posy or bouquet’), you’ll know how much time you need to schedule in advance of doing the whole event, and you can plan your floristry accordingly. I’ve said Wednesday and Thursday evening, but if you’re planning a smaller wedding you may be able to cut it all on Thursday evening. For a much bigger wedding, you’ll need more pairs of hands to help, because you don’t really want to be cutting your fresh garden flowers on Tuesday and expecting them to be perfect for the wedding on Saturday.

You do not need any more excitement than knowing that the flowers are grown and will be cut, and that the floristry will be done in plenty of time before the rehearsal.

Large arrangements can be spritzed with water to keep them looking ding-dong fresh – as if they’ve just been cut in a dew-drenched dawn.

Friday

So now all your flowers are cut. Your cool, airy, out-of-direct-sunlight place is filled with buckets of smiley flowery faces. If you’re going to make the bride’s bouquet and the bridesmaids’ posies and buttonholes, put the ingredients for those to one side and make sure they are clearly labelled, so an overenthusiastic helper can’t possibly use them to make posies for the portaloos.

Where to do the floristry?

I would advise that you do the floristry all in one place: somewhere cool and airy and out of direct sunlight. Don’t expect flowers to do well if you plan to arrange them in full sun outside in the heat of the day.

Once the flowers are done, put them somewhere cool and airy until it’s time to carry them down the aisle.

You’ll need a large clean surface for arranging on, and space to put the flowers when they’ve been done – another table, or a sideboard. You’ll also need something in which to transport the flowers to the venue: low-sided trays, such as old mushroom trays or baker’s trays, are ideal. Higher-sided boxes or crates might be needed to transport taller arrangements.

Collect useful-sized trays in which to transport your flowers when they’re ready.

Don’t plan to arrange your flowers at the venue: you’ll be double handling buckets and vases, you’ll make a mess you’ll have to clear up, and you may not be allowed to get into the venue until the day of the wedding – and you don’t want to be doing flowers so last-minute. Decide well in advance where the floristry will be done, and arrange the space to fit your needs. You may find that your neighbour’s house is better than yours, or that the garage, or a barn space if you have access to one, is ideal.

Timing

Start early. You will need more time than you think. Try to get the ceremony venue flowers done first, and if they’re to be used in a cool, stone church, you could send somebody off to deliver them and get them out of the way.

Do the table-centre posies and other reception arrangements next.

If you have a big enough team of helpers, then you can leave them to get on with all the above, so that you can do the bride’s bouquet, bridesmaids’ posies and buttonholes. Have vases, jugs or jars ready for the bouquets and buttonholes to be put in once they’re finished. Plan to be finished by mid afternoon, and then you will be finished by late afternoon.

Roses cut on the Thursday for a Saturday wedding will be half as open as this when cut. This photograph was taken on the Friday, after the bouquet was made. The rose would be fully open and perfect for the wedding ceremony.

Once the flowers are finished, take time to stand back and admire them. You’ll have done a wonderful job and saved yourself a merry fortune. Well done!

Top cutting and conditioning tips

Use clean scissors; clean buckets; fresh water. Bacteria are enemies of the cut flower.

Cut bulbs into their own containers, and keep separate from the other material until the next day.

In winter, cut foliage in the most clement part of the day.

In warm weather, cut in the morning or evening. Never cut flowers or foliage when you can feel the heat of the sun on the back of your neck.

Cut straight into water, so that the cellulose cells which sponge water up to the flower head never have time to dry up and stop working.

To keep the flower water clean, in hot weather you might want to add a drop of bleach to it to stop bacteria growing and spoiling the perfection of the flowers. We don’t recommend any kind of flower food, sugar, or dropping pennies in the water – though if that’s what your grandmother suggests, go with her – I wouldn’t want to try teaching anybody to suck eggs.

Leave flowers to have a nice long drink (condition) once they’re cut. Overnight is perfect. Then they’ll be ready to be used in your floristry the next day.

Whatever the time of year you are to be married, the first thing to do when planning your flower scheme is to look at what was in flower on that date the previous year (and the year before, and the year before that. . .). If your wedding is more than a year away, this is easier to do in the first instance, but it’s still worth taking the time to think back, and to talk to other experienced local gardeners, to work out which plants can be relied on.

What’s in the garden already?

Be sure to plan your wedding flowers around what you can forage from established gardens and other areas that are available to you, as well as on what you can grow. There will certainly be some good material to be found locally without your having to grow it all.

A cheerful mix of narcissi and tulips in a vintage pedestal vase is a happy combination for a simple table centre.

We have cut buttercups with a scythe at times, but even a handful brings a burst of sunshine into a spring posy.

This spring bride’s bouquet has apple blossom, cow parsley, cowslips and wild bluebells in it – all already growing in the garden before the tulips were planted for the wedding.

Fruit blossom

Fruit blossom goes over very quickly, so I wouldn’t advise basing your wedding flowers on the apple trees in the gardens you may have available to you. However, do be opportunistic, because fruit blossom is stunning, whether arranged as cushions in a vintage soup bowl as a table centre, or in tall sprays to frame the reception entrance. You can force tree blossom by taking prunings from mid winter and bringing them into the house. Put the stems in containers with a little water (which you must keep refreshed from time to time) and watch the blossom fatten up and begin to unfold. It’s difficult to control when the blossom will come out, but even if it isn’t out yet, the knobbly drama of lichened old apple-tree prunings makes a lovely frame to use as a base for your spring wedding floristry.

Apple blossom will happily be forced into flower when brought into a warm room.

The mix of what you might find in a spring garden might surprise you if you think about it. From apple blossom to forget-me-nots; to wild red campion, to bluebells, to cow parsley – here we even have early rose foliage, red edged and deliciously glossy, to use as greenery in a bride’s bouquet.

Tree and shrub foliage

Depending on the date of your wedding, you’ll have wonderful foliage of some sort exploding into leaf all over the place. I particularly love the acid-green fireworks of flowering oak, which are stunning mixed into an arrangement with cow parsley and tulips. Balsam poplar has a gorgeous scent that is reminiscent of honey, because bees use the stickiness of the buds to make propolis, with which they glue their hives together – but don’t use too much, because the smell can be overwhelming. Grey poplar has silvery leaves on silvery stems, while hornbeam and beech leaves will unfurl in the vase to make lovely delicate shapes in your floristry.

Keep an eye on all your shrubs and hedgerows: in spring they’re bursting with goodies that make good material for cutting. They may look dormant one week but be breaking into life the next. A few stems from any tree which looks as though it’ll be in leaf very soon – with fat, swelling buds on the stems – can be encouraged to leaf early by being brought inside into the warm.

Lilac can be lovely if it is in flower for your wedding, but be sure to sear it when you cut it (see Chapter 3), to stop it wilting. I find that spring, when many plants have fresh, sappy growth, is a time when I need to sear more than at any other time of year. With lilac, you should strip all the foliage bar the ‘bow tie’ of leaves just below the flowering head. Then snip the stem at a sharp angle and cut cleanly up it for a couple of inches before plunging the cut end into boiling water for 30 seconds or so.

Lilac will last much better in a cut-flower arrangement if the stems are seared when it is cut.

Some people are very superstitious about lilac and won’t have it in the house. Personally, I like to absolve any flower from unfortunate superstitious associations – which are hardly fair on the flower. What did lilac do to deserve such a bad reputation? But do check with Granny too, in case she has strong feelings on the matter and is likely to react alarmingly when she sees armfuls of lilac used in your wedding flowers.

Also flowering in late spring or early summer, the snowball bush (cousin of the wild guelder rose) gives us its fabulous spheres of greenish-white blooms. If the viburnum beetle doesn’t get its leaves, then the foliage is as useful – very fresh and green – as the flowers. It’s perhaps better for larger arrangements than for posies (just because it’s so useful as tall structure, and you might want to use the foliage as well as the balls of flowers), but don’t overlook it.

Look out too for flowering physocarpus (both the dark red and acid-green varieties), and the wild viburnum, the wayfaring tree, which has a very pretty flat umbellifer flower. All of the above will benefit from searing before use in floristry.

Some people hate its stink, but we also use choisya, which has wonderful glossy, evergreen foliage. We find that the smell disappears quickly after cutting and that it’s only the bruising of the stem in the cutting that makes for a short-lived unpleasantness.

Perennials

Aquilegia (columbine, or granny’s bonnets) flowers for almost 2 months from mid to late spring. Bistort, irises, early alliums . . . the garden is full of offerings at this time of year. Here at Common Farm, we use a great deal of the lovely dramatic, dark foliage of ‘Firecracker’ loosestrife in spring, to frame our floristry.

Do practise your arrangements in advance (see Part 3), to see if any of the ingredients you’re planning to use are likely to wilt. This is especially important in spring, as at this time of year the sappy growth can make plant stems very prone to flopping. Try searing wilty herbaceous cuttings, as you would for woody material (see Chapter 3), to see if they’ll stand up for you – it’s well worth making sure beforehand, rather than assuming that all will be well on your wedding day. That said, after an overnight drink in a bucket, floppy spring growth will often revive.

Wildflowers

Cowslips, cow parsley, red campion, forget-me-nots, buttercups, tellima, cuckoo flower (lady’s smock), wild snake’s head fritillaries . . . the meadows and hedgerows are full of flowers to cut in spring. It is perhaps the richest time of year for wildflowers. When brides call me and say “I’m getting married in late summer, and I want wildflowers everywhere,” my heart sinks slightly, as I know it’ll be a tougher forage for flowers that haven’t turned into seedheads. In spring, on the other hand, I know there will be an abundance.

Spring-flowering wildflowers are often perennial – all of the list above are, save forget-me-nots (biennial) and fritillaries (bulbs). They can also be very fussy about where they grow. You could buy them all as plants and put them in the ground the autumn before your wedding – tellima certainly makes a lovely border plant in the long term. Of the spring wildflowers, I’d say cowslips are the easiest to grow from seed – if you have enough notice, and can sow the seed the summer before you need them to flower. We grow cowslips to cut, and their scent in spring bouquets is one of my favourites during the whole cut-flower year. (See Resources section for a good supplier of UK native wildflower seed.)

This very simple bride’s posy has just-unfurling Spiraea japonica ‘Goldflame’ in it. (The bride didn’t really want to carry anything at all but I persuaded her that a tiny mix like this would give her something to do with her hands.) Without good conditioning that lovely foliage would wilt in a heartbeat.

Jam-jar posies ready for transporting to the wedding venue. These include a lot of wildflowers and freshly unfurling foliage, for a bride who wanted a very wild look to her flowers.

However, it is often the case that wildflowers prefer that unexpected corner under a hedge; the edge of a meadow; the wild grass in the orchard. In order to avoid disappointment, it might be best to identify in advance good swathes of the wildflowers you’d like to cut for your wedding, and if they are on land which doesn’t belong to you, then seek permission to cut them. Establishing enough cow parsley from scratch to cut for a wedding scheme could be very stressful; helping yourself from the half-mile of it edging the neighbouring farm may be the easier option.

We have found cowslips to be easy to grow from seed.

This tiny posy is made up of cowslips and cuckoo flower. The cowslips have a gorgeous, slightly bergamot scent, but the cuckoo flower does smell a bit cabbagey. I don’t mind this edge to the scent, but you may not love it. This posy is just inches high and wide – exquisite, but it won’t make a great focal point to your wedding scheme.

Weddings are often stressful occasions, with brides and grooms conscious that everyone’s looking at them – which is the point, but can still make one self-conscious when the actual moment of declaration looms. A single buttercup can give the nervous couple something gorgeous to look at; a distraction from the well-wishing crowd. I’ve had brides tell me that on the journey to the ceremony they just focused on the buttercup I put in their bouquet, and all the pressure disappeared and they remembered that the day was just about them, and their betrothed, and about their plighting their t

roth. Everything else – the table plan, the chair bows, the bridesmaids’ dresses, Great Aunt Winifred’s querulous request to sit as far away from her sister as possible – just faded into insignificance.

Of course, I do not advocate any kind of larceny: it is illegal to cut wildflowers in the UK from road verges, as this land belongs to the local council, and you shouldn’t steal from fields, even if the flowers are wild. But ask, and the farmer’s likely to say yes to you: who wouldn’t allow a bride a handful of buttercups for her bouquet?

THE BELTANE FLOWER

In the wild hedge you’ll also find hawthorn, or the May flower. You know that saying, ‘Ne’er cast a clout till May be out’? Well, that’s referring to hawthorn, which, in the UK at least, can flower earlier than May, and sometimes later. (The saying means ‘Don’t shed your winter clothes till the hawthorn is flowering.’) This lovely blossom and its leaves, which people eat as ‘hedge salad’ when they’re just unfurling, is also known as the Beltane flower, and in pagan times they would have made the original flower crowns with it and celebrated marriages using May flowers for all the decorations.

But do cut wildflowers last?

Some people say that wildflowers don’t last once cut. Allow me to differ. Cut wildflowers directly into water, when the day is still cool, and even buttercups should last a week. It’s true that wildflowers have more delicate stems than some of their cultivar cousins – but that means, simply, that one must take a little more care cutting them. Wildflowers in any season won’t take kindly to being kept out of water, and so won’t do well for long in flower-foam-based arrangements, but for a day or so they’ll be fine – although they are more difficult to use in flower foam because their stems tend to be too delicate for any pushing.

Grow your own Wedding Flowers

Grow your own Wedding Flowers